Journalism

in action

Illustration by Miguel Torres

Housing resources: expectations become barriers

People looking for help at shelters run into requirements that leave them frustrated and back out on the street.

Miguel Torres

Imelda Hartley and her 11 kids walked into an Avondale family shelter in the winter of 2010. They had escaped from domestic violence issues at home. Hartley, who was 39 at the time, had nowhere else to go with her children and had no family nearby. She expected a shelter would give her the stability to find her own place with her children, but found shelter programs difficult to stay in.

Shelters and housing resource programs share a goal: trying to end houselessness. They brand themselves as places where people who have been displaced can begin rebuilding their lives. To do this, they set up entry requirements and expectations for clients, but people who use their services sometimes feel set back by the established rules.

“We stayed once at a shelter that expected me and my kids to be back by 6 p.m. Between finding someone to take care of my kids and trying to work enough hours, there were times I couldn’t make it back in time. We had to find somewhere else to sleep those nights,” said Hartley, who is now 51 and pursuing a degree in social work.

“You’re trying to better yourself in that situation you are in, and sometimes, like whoa, all these rules seem to be barriers for betterment,” she said. “And then to try to bear domestic violence, it’s why so many, like I did, go back to their abusers. When we have to put up with this — those are barriers.”

Getting in and staying in

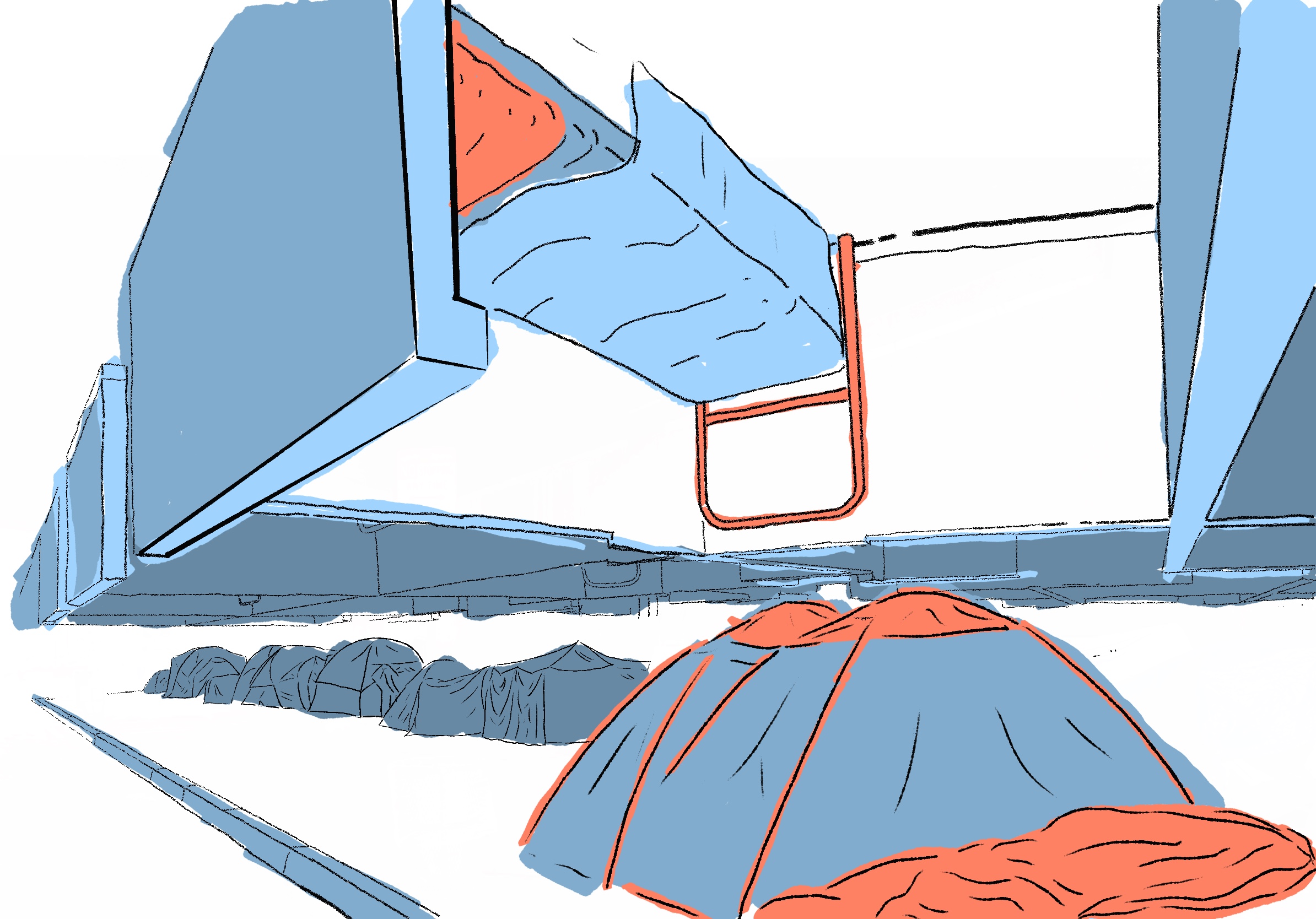

Illustration by Miguel Torres

Depending on the type of shelter, requirements for people staying there can focus on age, sobriety, criminal background or a limit on what one can bring in.

For example, most locations will do a criminal background check and disqualify a person if they have any convictions related to arson, sexual assault or violent crimes. In most cases, the reason is for the insurance they need, so they are not liable for any harm or damages that could happen at the campus.

Others like House of Refuge, a faith-based transitional program, require you to be sober and test for sobriety. Transitional programs focus on a person keeping a job and being able to support themselves by the end of the program. Some places that label themselves as residential living expect a person to stay on campus or in the house until they graduate from the program and enter rehabilitation from any substance use.

Other programs, like the Central Arizona Shelter Services (CASS), don’t require sobriety tests or background checks at its adult shelter. However, it does limit people to two bags per person and does not permit weapons or drugs on its grounds.

Once people meet the requirements to enter, these programs also have different rules and expectations.

Most programs have some sort of curfew requirement. At CASS, staff asks that people are at their beds at 8 p.m., while House of Refuge asks that people check in at 4 p.m. and be ready for dinner service at 5 p.m.

House of Refuge expects residents to attend one church service during the week and hold a day job where they work 32-40 hours a week.

Funding sources matter

Generally, there are three influences to how organizations determine policies: philosophy, funding and infrastructure, according to Jussane Goodman, Phoenix Rescue Mission’s director of community engagement.

“So, I think it all starts with funding,” Goodman said. “Depending on the type of funding that you’re receiving, is where a lot of your eligibility requirements are derived from.”

Nationally, most shelters and housing resource programs receive funding from federal grants through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), according to the Center for Poverty and Inequality Research at U.C. Davis.

“If you’re receiving particular funding and your funder, whether it be government or non-government, they could have specific criteria of what their dollars are allowed to be used for,” Goodman said.

For example, HUD’s Emergency Solutions Grants program, which focuses on helping people get access to housing or shelter, requires that someone “not have sufficient resources or support networks, e.g., family, friends, faith-based or other social networks, immediately available to prevent them from moving to an emergency shelter,” and “has an annual income below 30 percent of median family income for the area, as determined by HUD.”

Finding the right space to feel safe

There are many limits on resources, one of them being space. Some folks ache to have their pets stay with them overnight, but shelters need to have the space for them.

“What if the animal is not trained? What if the animal is not housebroken? What if the animal urinates inside of the facility?” Goodman said. “Then you have that impacting other residents that are staying within the shelter.”

Shelly, 44, finally found a place to stay with her 4-year-old black and white terrier, Madison, after searching for almost a year.

“She means safety to me, peace of mind when I’m laying down to sleep,” Shelly said.

Madison lay huddled in blankets spread out next to some grocery carts Shelly used to build a makeshift shelter. We stood 20 yards from the entrance to CASS in what is known as “The Zone.” It’s an area of about five blocks where folks camp hoping to get access to resources provided by CASS and the Human Services Campus.

After finding a place that accommodated Madison, Shelly still needed to figure out how to get Madison’s immunizations up to date.

“They told me I can’t have her there until those are updated. So until then, I’m sleeping out here with her,” Shelly said. “I wouldn’t be able to sleep inside without her.

Illustration by Miguel Torres

Being left out

All places offering shelter and other services have a working philosophy. Phoenix Rescue Mission’s values are faith-based: “We provide Christ-centered, life-transforming solutions to persons facing hunger, homelessness, addiction, and trauma.” They focus on helping families, single adults and people dealing with substance use disorder and domestic abuse. Other organizations focus on specific populations, like older people or teens, that limit to whom they provide resources.

“It just really comes down to the organization and their philosophical and/or targeted approach depending on which population they want to serve,” Goodman said.

For some people, finding space becomes complicated when they don’t meet a shelter or program’s baseline requirements.

At a group discussion on housing, Jesse, 30, white and male, talked about having a hard time finding the right housing program for him.

“They’re like … ‘Well, do you have a child?’ ‘No. No, I don’t have a child. I’m single.’ ‘OK. You’re male. Let’s see, what else? Do you have any extensive drug use?’ I was like, ‘Well no, I’m just a stranded traveler.’ It’s like, ‘OK, so rehab is completely out,’” Jesse explained. “And there’s been many times they’ve joked, ‘Oh, why don’t you get on those blue pills, just so you can get into rehab?’”

Jesse was stranded in Arizona after traveling to meet with a friend who had planned to give him a place to stay.

“It's just all of these little, little rules and regulations, and all these things just really put a damper on you actually being able to successfully move forward,” he said. “I'm not someone who wants to be on the street. I'm not someone who wants to be causing problems. I'm wanting to move on with my life.”

Changing the language

The National Alliance to End Homelessness presents an alternative to how shelters present their requirements. The group holds that there could be space for expectations and gentle guidance to “promote safety rather than attempting to control behavior.”

In a presentation by Technical Assistance Specialist Kay Moshier McDivitt, she explains how retooling “rules” to “guidelines” helps create a more inviting atmosphere.

“Look at the criteria that gets people discharged most often,” she said in the report. “Was this based on behavior that leads to safety concerns, or was it a behavior that could be managed but was handled by asking the client to leave?”

She suggested reducing barring or service restrictions to issues that lead to violence, excessive damage or theft.

Goodman talked about building programs with the clients in mind and viewing their work with customer service, client experience and user-friendliness as main focuses.

At Phoenix Rescue Mission they survey clients about their needs and experiences through their “Resource Gap Analysis.”

“It’s going to help to inform what us as an agency will do moving forward,” Goodman said. “As far as new programs, or new support, or new services, or relocation of services.”

Hartley thinks shelters need to be mindful of individual needs when they enforce shelter regulations, like curfew hours. She often talked to staff about wanting to make it into the shelter on time but couldn’t because of her work schedule.

“I get it, I understand why there are rules,” she added. “But there has to be times where you can just kind of bend the rules. Be mindful that people’s situations are quite different. Not all families are the same. Some might have only two children where some others have more than six. And that creates a huge difference.”

Mapping Blind Spots

Reporting on the sheltered and unsheltered communities requires transparency and collaboration between reporter and source in order to be beneficial.

An outreach and mutual aid volunteer sat in my kitchen while we cooled off from storing water coolers meant to be distributed in the summer. We drank some water and talked about a resource map I had been working on for the last few weeks. When I mentioned how the virtual map would track places where people could find water or camp without getting moved, her face grimaced slightly. She told me she had thought about this before but ran into problems.

Businesses in the area began to complain about not wanting their neighborhoods to be publicized as places for overnight stays. People camping on the street didn’t like that there were maps that law enforcement or others who would want to move them could use to find them. Hearing these concerns confirmed some of my fears. I was worried that I’d overstep and do some harm, and I felt glad for the reality check.

Traditionally when we as journalists report, we are told to keep our story close to the chest when interviewing sources. When it comes to community engagement reporting, my goal has been to share the process and get at journalism that helps community members directly. When it comes to the world of housing resources and shelters, there are people who are put in vulnerable situations daily. It was vital to me that I understood their fears about reporters sharing their stories and insights. This is where the type of reporting I wish to do differs from legacy or traditional reporting.

With context from stakeholders, I reworked the resource map and built it so that people who are using those resources can add their input. When I first built it, I hoped that the map would be the centerpiece of my reporting, but it was the process of making that map that became the heart of this story.